|

Man stands ground in face of state

requests

(Note: While this AP reporter and others simply will not report --

or is not allowed to report -- is that this is part of the nationwide

Wildlands Project, a monstrous landgrab under the guise of 'rewilding',

'rewetting' or 'restoring' everything but a few urban centers to a

'vision' of what it was the day before Christopher Columbus set foot

on America's shores. It is just a ploy to take back America's

resources from those that earned them, like Jesse, and maybe one day

soon, like you...)

July 4, 2004

By Jill Barton

The Associated Press

To submit a Letter to the Editor: [email protected]

Naples, Florida - Out in a scrubby patch of former swampland, Jesse

James Hardy owns everything under the sunrises that stretch from a

horizon of slash pine and palm trees.

He owns all that's under the stars in the summer sky, including the millions of mosquitoes and gnats that swarm the still air.

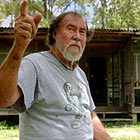

Sticking

to it. (J. Pat Carter/The

Associated Press)

July 4, 2004

Land.

(J. Pat Carter/The Associated

Press)

July 4, 2004 He owns a well he dug 60 feet down that provides what he calls the best-tasting water in Florida. And he owns a simple clapboard house that he built himself -- after a wildfire tore apart the last one. "It ain't been an easy life, but I love it. I really do. This is my home," said Hardy, a 68-year-old former Navy SEAL. "I couldn't trade it for nowhere else. It's irreplaceable."

But Hardy's 160 acres sit in the path of what is perhaps the nation's

most ambitious environmental project ever, a 30-year effort to restore

the natural water flow to the Everglades.

For years, state officials have quietly negotiated with Hardy to come up with a price for a piece of land that many consider worthless -- and one man considers priceless. He has adamantly refused, even as the offers have doubled and tripled into the millions of dollars. Restoring the Everglades means turning Hardy's land back into its natural state as a flooded plain, before farmers and developers backfilled, dredged and carved canals through an ecosystem that once stretched uninterrupted from a chain of lakes near Orlando to the Florida Bay. "There's a lot of overwhelming public benefit," said Ernie Barnett, the state Department of Environmental Protection's director of ecosystem projects.

But Hardy insists he's staying put, even if it means passing up

millions.

"It's nothing fancy, but what I'm telling you is, I live all right," he said. "I don't have to have gold-plated plumbing to take a shower. I got it better than people living in town. Of course, a lot of people won't live like this." Hardy's homestead on the edge of what were once Everglades wetlands is hidden 40 miles east of downtown Naples but seemingly a million miles from the development of Florida's southern coasts. Hardy bought the property for $60,000 in 1976. "I bought it because it was cheap ... ," Hardy said. "There wasn't any people here. It was just very serene, clean, fresh, quiet. It was just a real beautiful place." Since then, Hardy has tamed his wilderness, largely for a 9-year-old boy he considers his son. Tommy Hilton and his mother, Tara, a family friend, came to live with Hardy five months after the boy was born. Hardy said he and Tara are not romantically involved. She works for him, helping him check the trucks that buy the lime rock off his property and haul it away. Disability from the military covers the rest of the bills. A few years back, when the Everglades restoration was just a proposal, the state offered Hardy $711,000 for the property. Hardy still seems insulted. "They're wanting to get all the humans off the land and turn it back to wildlife, and they don't even know if it's going to work," he said. "They want to take this away from me and that little boy." State officials have kept trying, offering to swap his land with a similar stretch a little farther from the Everglades. They gradually upped their offers until last month when it reached $4.5 million -- a figure state officials acknowledge is probably more than the land is worth. The millions seem like pennies compared with the overall $8.4 billion restoration -- a project that aims to link a vast ecosystem of tranquil waters, saw grass and towering cypress trees. Once restored, Hardy's property and the surrounding areas would rejoin Picayune Strand State Forest and link four valuable reserves that surround it, including the Florida Panther Wildlife Refuge and the 10,000 Islands National Wildlife Refuge. "The overriding importance is that the entire Everglades Restoration Plan requires this parcel to get started," said DEP's Barnett. "We're plugging canals to restore the natural water flow, and his land will no longer be dry. He would be flooded, and we cannot legally allow anyone on private property to be in harm's way." Officials have recently threatened to seize the land under eminent domain, which allows government to take private land for a public purpose. Governor Jeb Bush and environmental officials have said they want to avoid going to court. But this land has become Hardy's life. He shows off the pond he hopes to turn into a fish-farming business, and another where he and Tommy fish in the shade. "The Everglades is 60 miles east of here. This has nothing to do with the Everglades," Hardy said. "I'm out here. Nobody even knows. Please, tell them, 'Please, just leave me alone.' That's all I want." http://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/local/state/orl-locglades04070404jul04,1,2692940,print.story? coll=orl-home-headlines (subscription)

A swamp home that's priceless

Man turns millions down to keep home

It's Not Money That Matters to Florida Man

http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/nation/la-adna-everglades4jul04,1,6395346.story?coll=la-home -nation (subscription)

Man refuses millions in battle to keep swampy home

On the Net: Jesse Hardy's Web site: http://www.jessehardy.com Florida Department of Environmental Protection: http://www.dep.state.fl.us Everglades Restoration plan: http://www.evergladesplan.org http://www.propertyrightsresearch.org/wildlndsprjctfrms.htm http://www.propertyrightsresearch.org/everglades/evergladesfrms.htm |